|

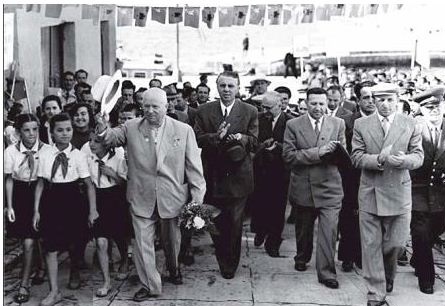

| Nikita Khrushchev in Tirana in 1959 and to his left Enver Hoxha, Mehmet Shehu and other communist leaders of the time |

The visit to Albania by the leader of the former Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, in 1959 is also remembered for the stories related to his comments about wheat cultivation.

Khrushchev told Albanian leaders that "the amount of wheat Albania produces is eaten by the mice in the Soviet Union's granaries."

|

| Nikita Khrushchev planting orange trees with Enver Hoxha in Saranda, July, 1959 |

He added that Albania should not exert such great efforts and resources on wheat production, considering that its price in foreign markets was low. He suggested to Albanian counterparts that instead of wheat, they should "plant fruits and citrus."

Later on, his advice would be interpreted by Albanian counterparts, within the prevailing dogmatism and paranoia of the time, as a devilish attempt to keep Albania dependent and enslaved.

Despite the intentions and interpretations, Khrushchev's comments had an economic logic. The massive cultivation of wheat during the communist era was linked to self-isolation, and domestic bread production implied the possibility of political and ideological independence.

Wheat is an agricultural crop where economies of scale are particularly relevant. Cultivating large areas with wheat leads to cost reductions per unit tied to labor costs, agricultural machinery, chemical fertilizers, etc. Not coincidentally, the world's largest wheat producers are those countries with vast open fields available for cultivation.

Due to its small territory and predominantly hilly and mountainous terrain, Albania lacks this advantage. It didn't have it during the communist era, and even more so today, when fragmentation and parceling of farmland are significant factors limiting competitiveness, especially for those crops where economies of scale are particularly crucial.

In this sense, it's not surprising that in the decades after communism, agricultural production shifted more towards the cultivation of vegetables and fruit-bearing trees.

Wheat production was mostly destined for the family consumption needs of farmers, while the use of domestic production in the industrial processing chain remained minimal. In 2021, Albania imported 41.2% of its wheat from Russia, 32% from Serbia, and 4% from France.

However, Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022 brought disruptions to the wheat markets and caused an increase in their prices, given that both conflict-involved countries are major global producers.

Some countries even suspended wheat exports, creating concerns that import-dependent countries wouldn't meet their needs. This prompted Albania to refocus on wheat production and launch a subsidization program for its cultivation.

Meanwhile, the geography of imports changed, adapting rapidly to new market conditions. For the first seven months of 2023, around 37% of wheat imports came from Serbia, 17% from Russia, and 14.5% from Ukraine, according to INSTAT.

However, the situation in the wheat markets settled within a few months, especially after an agreement was reached for wheat exports from Ukraine. Prices began to decline.

This year, during harvest time, wheat prices experienced a significant drop. This led to low prices offered by wheat processing factories for domestic production, which would result in losses for farmers if sold at those prices.

According to some farmers, state aid through direct subsidies for cultivation and fuel covered only a very small portion of their expenses, around 3%. This has caused production to remain stagnant, and farmers still lack a solution.

The wheat situation should serve to draw conclusions about agricultural production incentive policies. Wheat has rarely been a highly profitable crop for Albania's conditions, even less so in a period where the prices of agricultural inputs have increased significantly.

When the government encourages farmers to plant a crop that typically isn't profitable, in the name of food security, then it should take on the risk of price fluctuations and purchase the wheat itself for the country's reserves.

The practice of creating strategic reserves of essential products by the state is not uncommon.

Neighboring countries in the region have followed similar practices, instituting mechanisms for state wheat procurement when product prices don't provide minimal coverage of farmers' expenses.

If the Albanian government doesn't undertake such protection for farmers, at the very least agricultural policies should not be driven by emotional reactions and panic induced by temporary developments in global markets.

Such incentives, especially with insufficient subsidies, are causing significant economic harm to farmers and exacerbating the problems of a sector facing difficulties due to fragmentation, property title issues, poor access to financing, and an increasingly severe labor shortage due to emigration and population decline.

Source: Monitor